El uso continuo de Internet en la profesión del traductor: ¿aliado incondicional o enemigo silencioso?

Todos sabemos que el advenimiento de la red informática mundial, mejor conocida como Internet, ha sido, quizás, el avance tecnológico más importante desde la invención de la imprenta, simplificando y acelerando la búsqueda de información de maneras inimaginables hasta hace unas décadas. Lo que tal vez sea novedad para algunos es que ya están empezando a sentirse sus consecuencias nefastas en la capacidad de atención y concentración y en la memoria de quienes usan Internet de continuo. En este sentido, los traductores no somos la excepción: tanto para los que nacieron en la era digital como para los que fuimos testigos asombrados de los actuales avances en tecnología de la información, el uso de Internet en nuestra profesión es imprescindible y ya no podemos imaginar trabajar de otro modo. Es más, los límites son bastante difusos y tampoco podemos imaginar prescindir de Internet en nuestra vida personal. Tendremos que hallar maneras de evitar que ello nos lleve a prescindir de funciones básicas de nuestro cerebro.

La labor del traductor, en cifras

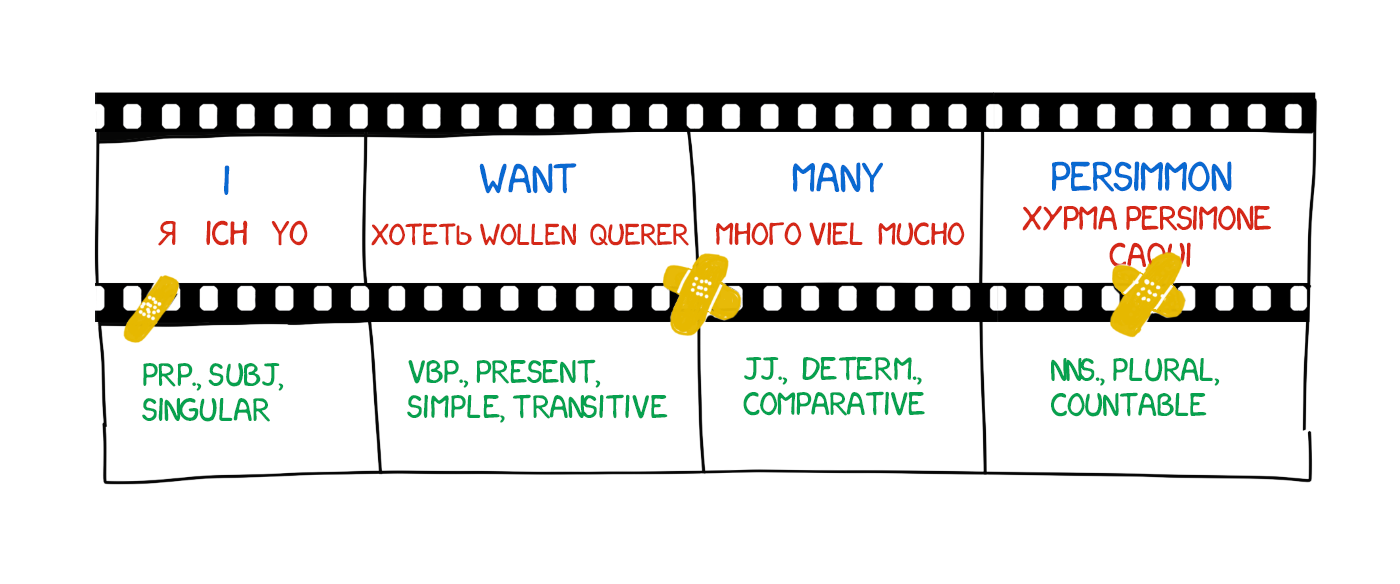

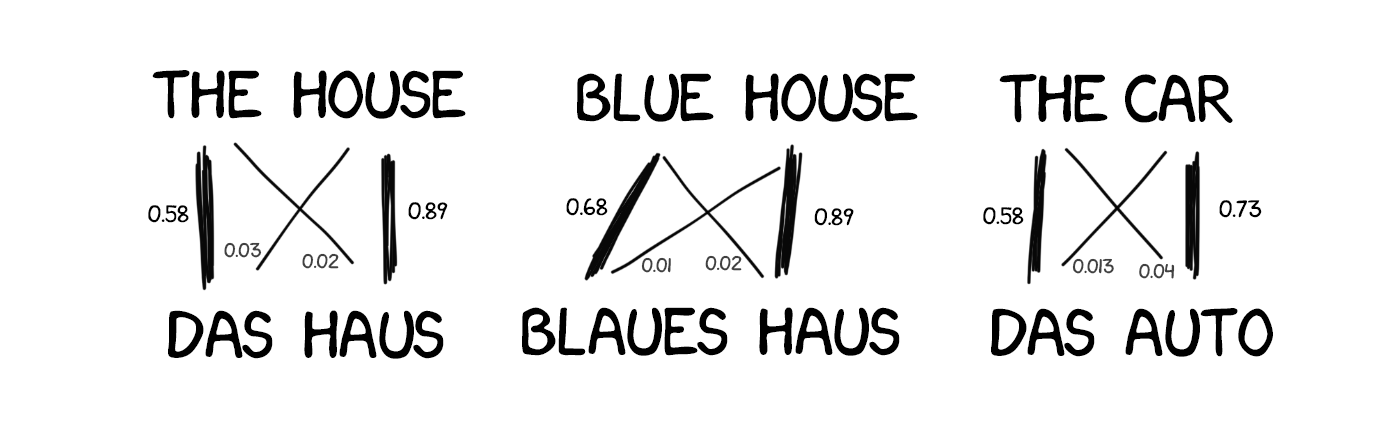

Un traductor típico traduce habitualmente tres mil palabras por día; puede decirse entonces que, en promedio, la cantidad de palabras que traduce por hora es de aproximadamente trescientas y, por minuto, de alrededor de cinco. Esto significa que los traductores tomamos al menos dos «microdecisiones» terminológicas por minuto mientras trabajamos, y que la cantidad de microdecisiones de este tipo que tomamos en un día cualquiera es de alrededor de mil doscientas.

Mil doscientas veces al día nos entregamos al desafío de encontrar en nuestra lengua el equivalente a una palabra en un idioma extranjero o viceversa. Si el texto que estamos traduciendo no nos es absolutamente familiar, o si no está escrito de manera clara y coherente, la magnitud de ese desafío puede multiplicarse exponencialmente.

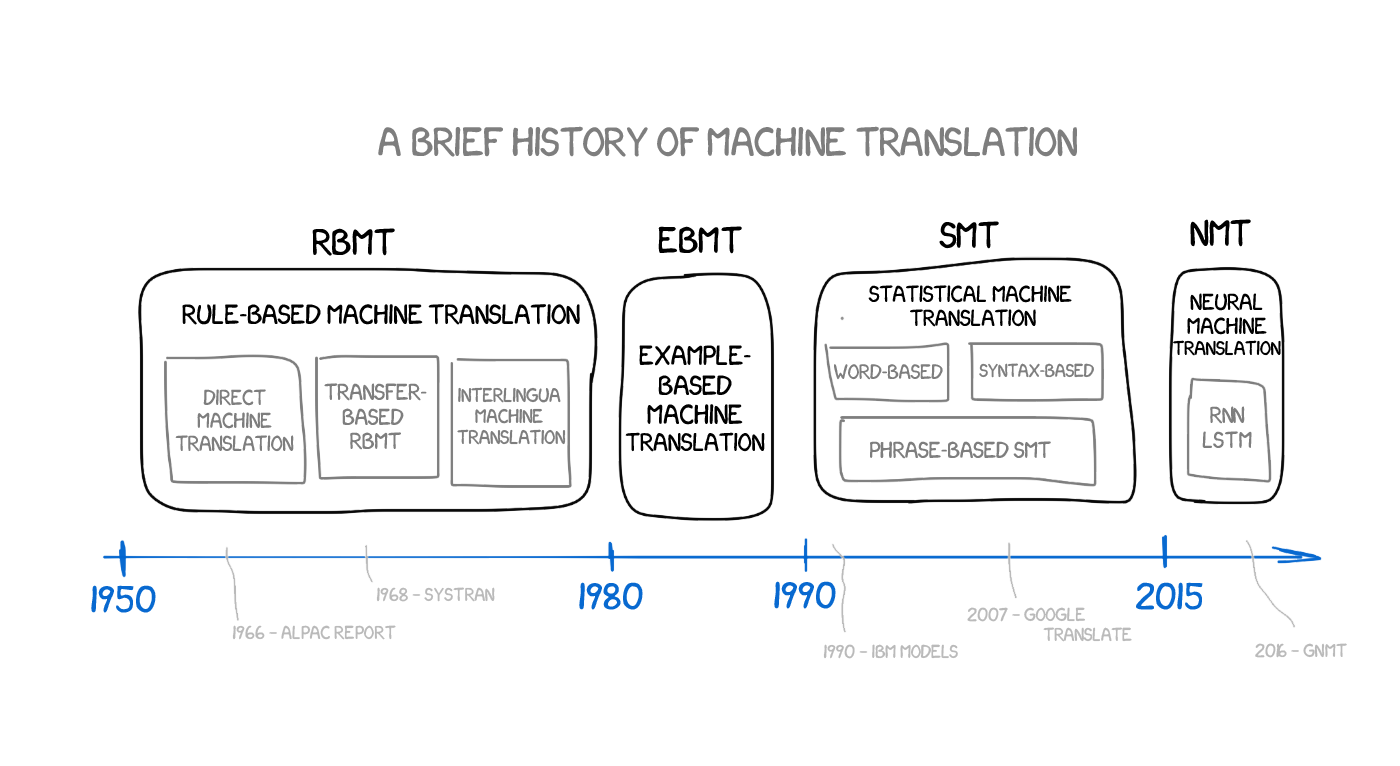

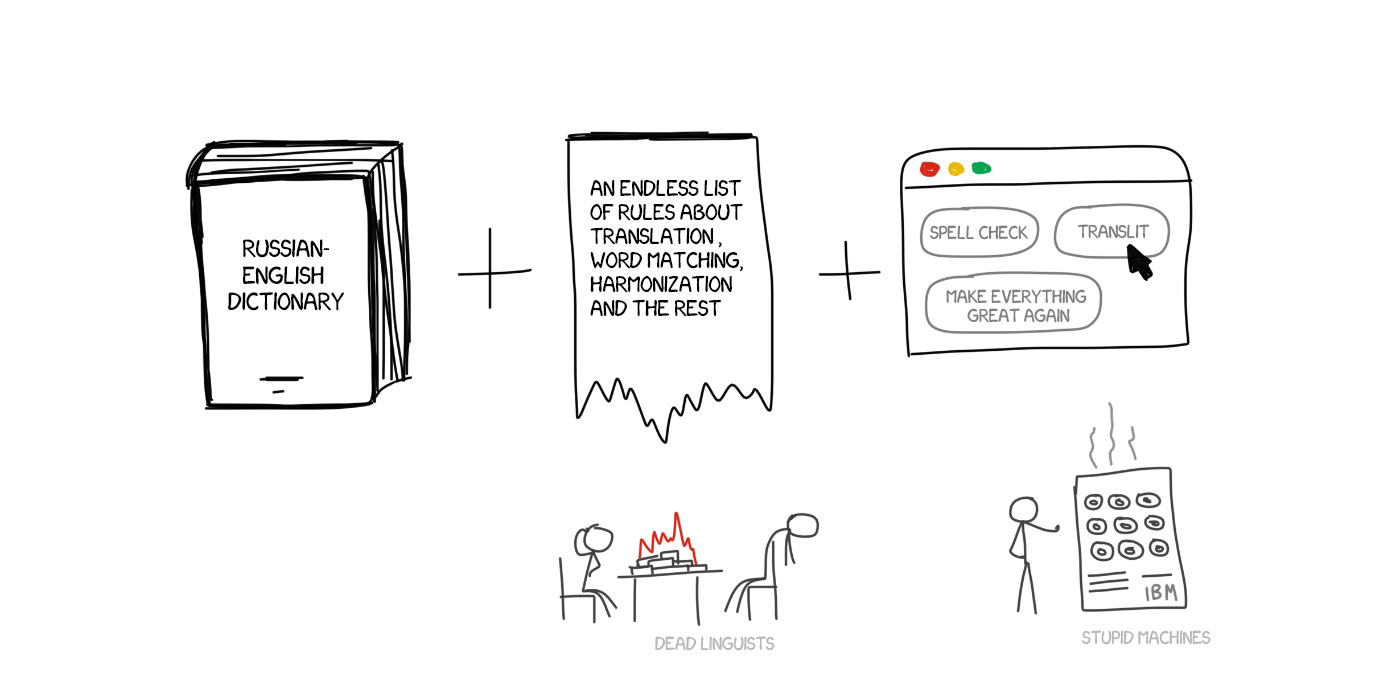

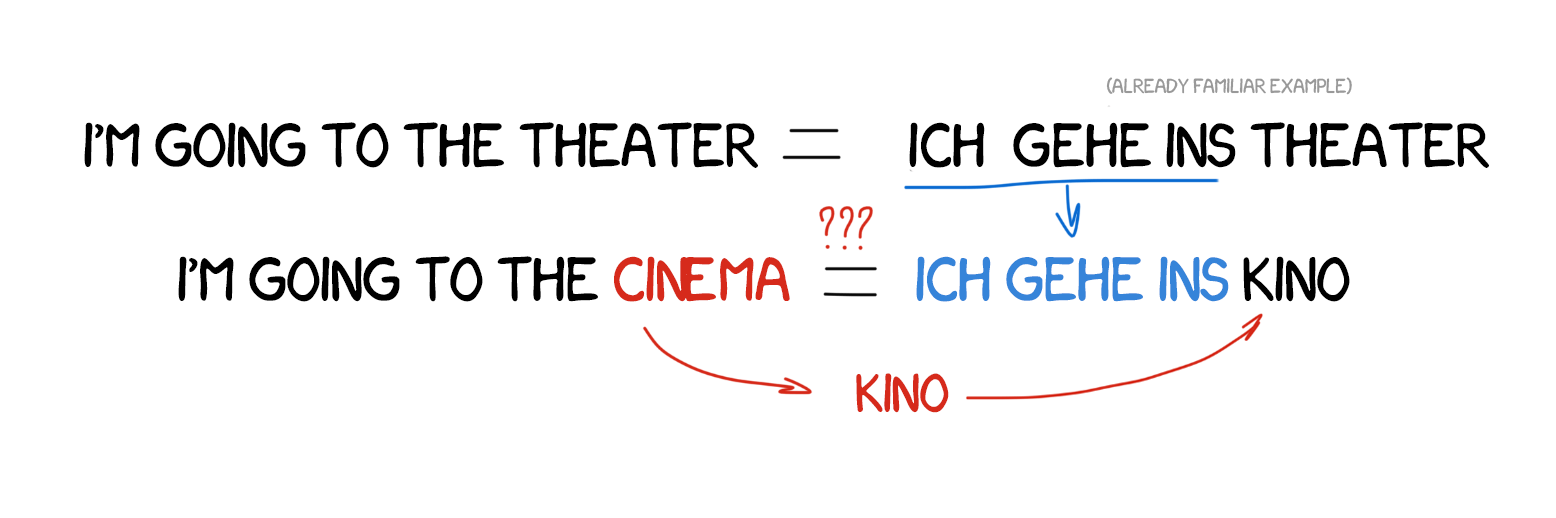

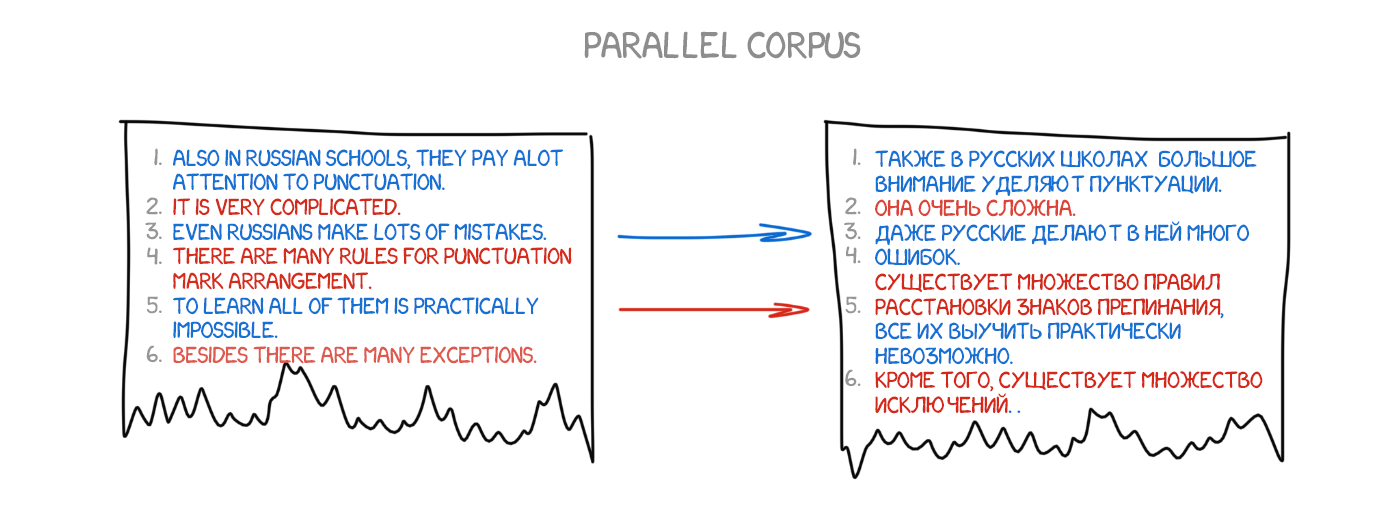

Es aquí es donde entra en escena el recurso que ha transformado más profundamente la labor de investigación del traductor: el uso de Internet. Para los traductores experimentados, dedicados a un campo de especialización específico, es relativamente sencillo encontrar fuentes de información confiables que nos permitan trabajar con mayor rigor y celeridad. El uso de Internet es un recurso prácticamente indispensable, por ejemplo, en la compilación de corpus lingüísticos de especialidad, una de las herramientas de uso habitual en nuestro trabajo, que nos permite determinar cómo se expresan y escriben los especialistas.

En la actualidad, sería impensable traducir sin un acceso a Internet rápido e ininterrumpido. De hecho, muchos nos aseguramos de tener más de un proveedor de servicios de Internet como parte de nuestro plan para contingencias. Lo que muchos de nosotros nunca previmos es que las mil doscientas microdecisiones que solemos tomar diariamente en nuestras diez horas diarias de conexión, durante cinco, seis o siete días a la semana, terminarían cambiando la manera en que funciona nuestro cerebro, nuestra habilidad para recordar rápidamente datos básicos y nuestra capacidad para concentrarnos en lecturas relativamente cortas.

Efectos negativos de la facilidad de acceso a la información

Desde tiempos inmemoriales, el ser humano siempre ha confiado no solo en la información almacenada en su propio cerebro, sino también en los datos específicos de cuya preservación son supuestos responsables otros miembros de su grupo social. En el hogar, por ejemplo, puede ser la madre la que habitualmente recuerde las fechas de cumpleaños de toda la familia y el padre el que sepa qué club de fútbol quedó en tercer lugar en el campeonato mundial hace diez años.

Esta distribución de la memoria evita la duplicación innecesaria de esfuerzos y sirve para ampliar la memoria colectiva del grupo. Al desligarnos de responsabilidad por cierto tipo de información, liberamos recursos cognitivos que, de otra manera, hubiéramos tenido que utilizar para recordar esa información, y los usamos para incrementar la profundidad de nuestros conocimientos en las áreas de las que nos consideramos a cargo.

Ya Sócrates se quejaba de que los libros eran enemigos de la memoria, dado que los individuos, en lugar de recordar las cosas por sí mismos, habían comenzado a depender de la palabra escrita. Actualmente, a todos los fines prácticos, ha dejado de ser eficiente usar el cerebro para almacenar información. Debemos reconocer que el uso casi permanente de Internet tiene efectos formidables en nuestra vida. Hay quienes comparan Internet con un «cerebro fuera de borda» o un disco rígido externo, con una capacidad de memoria muy superior a la que tiene —o necesita— un cerebro humano, y preocupa a los investigadores que sea tan adictivo como el alcohol o el tabaco, alentando el mismo tipo de comportamientos compulsivos.

La facilidad para acceder a la información, una de las ventajas fundamentales del uso de Internet, está teniendo hondos efectos en nuestra capacidad para retener la información adquirida. Se han realizado estudios que indican que puede alterar los mecanismos del cerebro responsables de la memoria a largo plazo. Según Elias Aboujaoude, doctor en medicina, psiquiatra e investigador de la Universidad de Stanford, «¿Para qué preocuparnos por recordar cuando tenemos toda la información a un clic de distancia? Memorizar se ha transformado en un arte perdido».

Hoy en día, podemos acceder instantáneamente a la totalidad de la memoria humana a través de Internet con solo realizar una búsqueda rápida. Muchos afirman que, a causa de esta inmediatez, Internet está menoscabando nuestras facultades cognitivas, socavando el impulso de guardar información en nuestros propios bancos biológicos de memoria, en lo que se ha dado en llamar el «efecto Google».

En su controversial artículo Is Google Making Us Stupid?, Nicholas Carr, escritor norteamericano, experto en las nuevas tecnologías de la comunicación, afirma: «En los últimos años, he tenido la incómoda sensación de que alguien o algo ha estado jugando con mi cerebro, reestructurando mis circuitos neuronales, reprogramando mi memoria. Hasta donde puedo decir, mi mente no está fallando, pero definitivamente está cambiando».

Dos plagas de la era de la información: la sensación de saber y el fenómeno de la punta de la lengua

Dos de los fenómenos más notables causados por el uso continuo de la tecnología para acceder a la información son la incómoda sensación de saber (convicción de que se posee cierta información a pesar de no haber podido recuperarla de la memoria en un momento determinado) y el fenómeno de la punta de la lengua (estado similar a la sensación de saber, pero en el cual la recuperación se percibe como inminente).

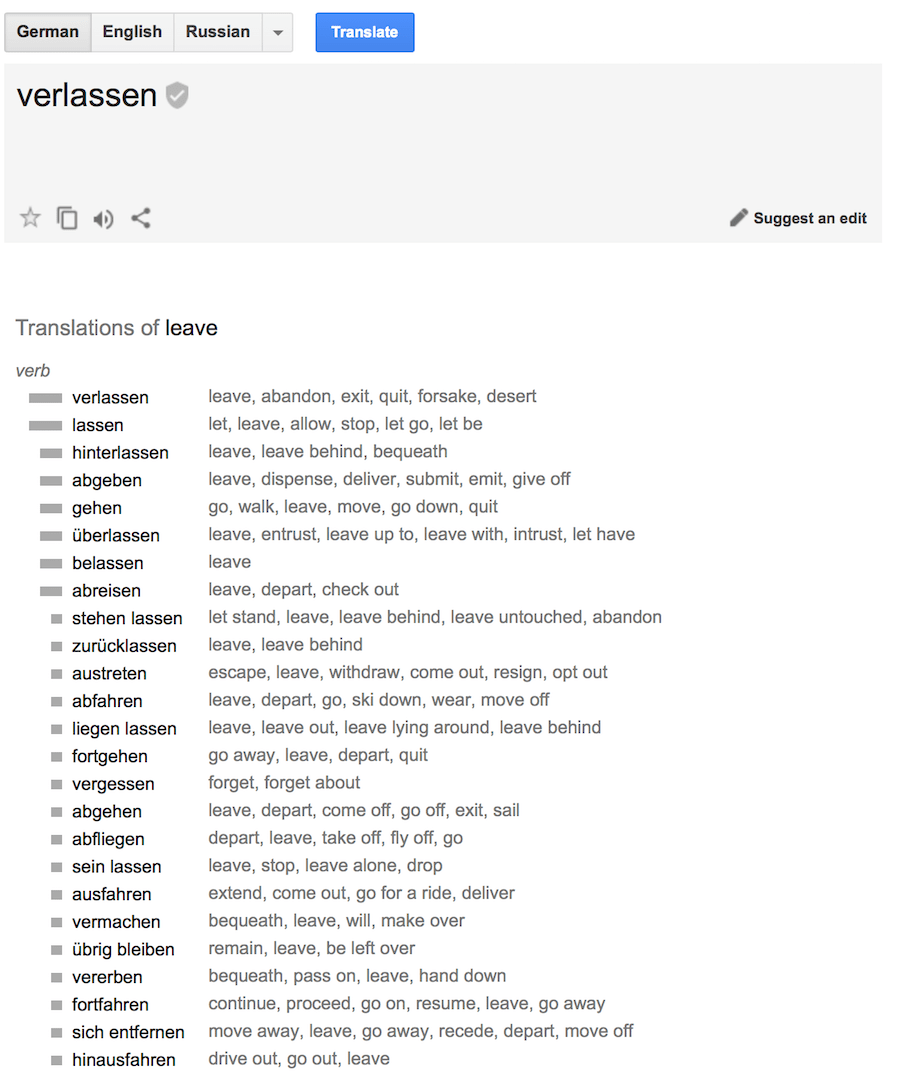

Los traductores hemos dejado de esforzarnos por recordar datos, para tratar de acordarnos de cómo y dónde encontrarlos. Si se nos pregunta, por ejemplo, por la traducción de una parte específica y poco conocida del cuerpo humano y no la recordamos inmediatamente, lo más probable es que nuestra reacción inicial no sea pensar en la anatomía humana en absoluto, sino tratar de ver cómo resolver nuestra duda a través de Internet. Además, hay estudios que demuestran que, una vez hallado el dato que buscamos, tendemos a memorizar no el dato en sí mismo, sino cómo y dónde lo hemos encontrado para franquear más fácilmente esa dificultad si vuelve a presentársenos más adelante.

Efectos negativos de la adaptación al exceso de información

Ya dando por sentado el hecho de que los traductores recurrimos casi automáticamente a realizar una búsqueda en Internet antes de sondear nuestra propia memoria, debemos admitir que la enormidad de la información disponible en Internet supera nuestra capacidad para asimilarla, al menos en un lapso razonable. Es así que comenzamos a utilizar, muchas veces intuitivamente, una serie de técnicas que nos permiten adaptarnos a tal exceso de datos.

Entre las más comunes se destacan:

- la lectura exploratoria (skimming), una lectura rápida y activa, focalizada en determinar cuál es la idea general del texto; utilizamos estrategias como ubicar palabras clave y valernos de ayudas tipográficas (texto en negrita, texto resaltado, títulos, subtítulos, gráficos y sus encabezados);

- la lectura analítica rápida (scanning), una lectura orientada a buscar los datos deseados, ignorando el resto del contenido; en este caso, lo que hacemos es «barrer» el texto con la vista, buscando nombres propios u otras palabras, números, fechas u otros datos específicos.

Ocasionalmente, también recurrimos a lo que podríamos llamar una vista previa, que nos ayuda a determinar si el material es apropiado y puede resultarnos útil. Las estrategias que utilizamos en este caso incluyen examinar el título a fin de realizar conjeturas acerca del contenido del material, determinar el nombre del autor, la fecha de publicación, etc., para sacar conclusiones acerca de si el material es pertinente, leer el prólogo o la introducción en búsqueda de información relevante, o revisar el índice para hacernos una idea general del contenido.

Estos métodos hacen que podamos acceder a una gran cantidad de información en un espacio de tiempo mucho más breve, pero se está llegando a la conclusión de que, a la larga, estos hábitos de lectura nos impiden concentrarnos largo tiempo en la lectura y nos hacen más propensos a la distracción.

Si bien esto no afecta mayormente el proceso de traducción en sí mismo, de por sí ágil y muchas veces caracterizado por intensas descargas de adrenalina, empieza a notarse, sí, cuando nos enfrentamos a la corrección o revisión de un texto, propio o ajeno. Es posible entonces que apliquemos automáticamente, casi sin darnos cuenta, estos mismos métodos de lectura, con las consecuencias que pueden inferirse rápidamente. Muchas veces nos descubrimos leyendo un texto «a vuelo de pájaro», cuando deberíamos estar haciendo una lectura detenida y cuidadosa, palabra por palabra, prestando atención a signos de puntuación y errores que podrían burlar las defensas del corrector automático. La lectura rápida puede transformarse en nuestro peor adversario cuando trabajamos como correctores o revisores.

También se está empezando a percibir que estos hábitos de lectura, que tan útiles nos resultan en nuestro trabajo, van impregnando poco a poco también nuestra vida personal. En este ámbito, podemos llegar a encontrar difícil leer noticias o artículos extensos e incluso libros, e impacientarnos cuando nos hallamos ante argumentos largos. A estas alturas, la búsqueda perentoria de información se convierte para nosotros en algo así como una obsesión. La misma tecnología que nos permite ser cada vez más ágiles también nos va llevando a tener comportamientos cada vez más rígidos.

Cómo contrarrestar, al menos en parte, el efecto Google

La buena noticia es que, si nos lo proponemos, podemos revertir, aunque sea parcialmente, estos efectos.

Las herramientas más útiles parecen ser evitar en lo posible la lectura rápida e irreflexiva, concentrándonos en realizar una lectura profunda y atenta y haciendo un esfuerzo consciente por consolidar la información. En otras palabras, evitar la distracción y alimentar la memoria a largo plazo[1], los dos aspectos más afectados por el uso constante de Internet en nuestro trabajo diario.

Tengamos en cuenta que, además de ser placentero, leer profundamente estimula el almacenamiento de información en la memoria. En su ensayo Traducción – Interacción: lecturas interactivas e interaccionales como preparación a la traducción, Jeanne Dancette habla de la utilidad de «resumir, detenerse en los obstáculos dando marcha atrás para verificar o aclarar un punto, y hacer anticipaciones o predicciones sobre el texto». Estos pueden ser buenos puntos de partida para [volver a] desarrollar nuestra capacidad lectora y, tal vez, recuperar nuestro antiguo placer por la lectura.

Hagamos un pequeño paréntesis aquí para reflexionar acerca de cómo llevar esto a la práctica traductora, tanto en que respecta a la atención en la lectura como a la consolidación de la información en la memoria a largo plazo y el uso de nuestros propios recursos internos.

- Si bien todos sabemos de la urgencia que caracteriza la mayor parte de nuestros encargos, leer atentamente el texto y detenernos en los obstáculos que pueda presentar antes de comenzar a traducir podría ser una excelente manera de encarar cualquier trabajo. Muchos ya lo hacemos habitualmente, pero a todos nos serviría para comprender profundamente el texto antes de pretender volcarlo fielmente a la lengua de destino.

- También sería sumamente útil perder unos minutos, o incluso solo unos segundos, tratando de recordar términos o expresiones que ya conocemos —o, si esto no es posible, hacer algún tipo de anticipación o predicción— antes de realizar una búsqueda en Internet.

El hecho de realizar el esfuerzo de memorizar sirve para reeducar el cerebro, ya que modifica nuestras sinapsis cerebrales de modo de poder aprehender ideas y habilidades nuevas no solo en el momento presente, sino también en el futuro.

Para lograr este almacenamiento de información en la memoria a largo plazo se requiere pasar por un proceso conocido como consolidación. Si la información no se consolida, se olvida. Almacenar datos y establecer conexiones entre ellos requiere un alto grado de concentración y compromiso intelectual o emocional. Si utilizamos Internet sistemáticamente como recurso inmediato para sustituir el uso de nuestra propia memoria, sin atravesar el proceso interno de consolidación, no tardaremos en ver los resultados en nuestra memoria a largo plazo.

Por último, es interesante recordar que, dada la manera en que funciona el cerebro, la generación de recuerdos duraderos es un proceso que requiere del transcurso de varias horas y ocurre fundamentalmente durante el descanso. Es por ello que descansar apropiadamente también es esencial para no olvidar lo aprendido.

Conclusión

Cuanto más usamos Internet, impulsados velozmente de una página a otra por motores de búsqueda e hipervínculos, más entrenamos al cerebro para la distracción, para el procesamiento rápido y eficiente de la información, pero sin una atención sostenida. Tratemos de actuar rápidamente para evitar que esto nos afecte permanentemente y recordemos, por último, que para el cerebro humano —que no para las computadoras— el cielo es el límite.

Nota al pie

[1] Podemos hablar de tres tipos de memoria: la memoria sensorial, que puede durar unos segundos y se hace evidente, p. ej., al «recuperar» de la memoria algo que acabamos de escuchar, tras la apariencia de no haberlo comprendido; la memoria a corto plazo, que puede durar unos minutos e incluso horas, y la memoria a largo plazo, que puede durar años.

Este artículo también puede leerse en inglés:

Keep yourself from losing your memory to the Internet

Unplug. Slow down. Search your brain.

Agradecimiento:

Imagen publicada con permiso del autor, el fotógrafo Salvatore Dore: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jmind2_0. Todos los derechos reservados.

Referencias bibliográficas

American Psychological Association, APA, 2010. APA. Diccionario conciso de psicología. 1st ed. Colombia: Editorial El Manual Moderno.

Carles Soriano Mas, 2007. Fundamentos de Neurociencia/ Fundamentals of Neuroscience (Manuales/ Psicologia) (Spanish Edition). Edition. EDIUOC.

Greenblatt, A., 2010. Impact of the Internet on Thinking: Is the Web Changing the Way We Think? CQ Researcher, [Online], Volume 30, Number 33, 773-796. Available at: http://www.sagepub.com/ritzerintro/study/materials/cqresearcher/77708_interthink.pdf [Accessed 18 May 2015].

Lecto-comprensión de la lengua inglesa. 2012. Textos en inglés y en español: elementos en común. [ONLINE] Available at: http://monterofabiana.blogspot.com.ar/2012/10/teoria-y-actividades.html?view=magazine. [Accessed 18 May 15].

Nicholas Carr. 2008. Is Google Making Us Stupid? What the Internet is doing to our brains. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/07/is-google-making-us-stupid/306868/. [Accessed 17 May 15].

Nicholas Carr, 2011. Superficiales (The Shallows) (Spanish Edition). Edition. Taurus.

Rodríguez, E. (2003). La lectura. Cali (Valle, Colombia): Programa Editorial Universidad del Valle.

Wegner, Daniel M. et al, 2013. The Internet Has Become the External Hard Drive for Our Memories. Scientific American, [Online], Volume 309, Issue 6 , N/A. Available at: http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-internet-has-become-the-external-hard-drive-for-our-memories/?page=1 [Accessed 18 May 2015].